|

Summer

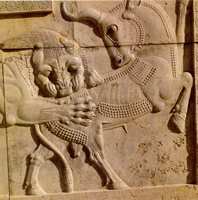

vanquishes winter Frieze at Persepolis |

In the temperate zones of the northern hemisphere, the spring equinox signals the beginning of warmer weather and the season for plowing and the sowing of crops. ‘New day’ in Persian is noruz, and the festival of that name marks the beginning of the year, which is still celebrated at the equinox in modern-day Iran. Persian mythology credits the mythical King Yima—Jamshid, the most famous of the prehistoric Iranian kings—with the creation of the calendar; as a result, Zoroastrians of Iran have given the name Jamshedi Noruz, “the New Day of Jamshid”, to the New Year observance.*

As is typical of mythic hero-kings, Jamshid is also credited with the invention of most of the arts and sciences on which civilization is based—not to mention the construction of the ancient city of Persepolis,** the ruins of which are replete with astronomical and spiritual symbolism. In Zoroastrianism, light is the great symbol of God and goodness, whether witnessed in the light of the sun or in the sacred fire at the heart of the temple. The lengthening of days which occurs after the spring equinox is thus perceived as a symbol of the victory of light over the darkness of winter, a victory that is represented symbolically at Persepolis by the defeat of the bull of Taurus—the astrological constellation that rules during the rainy period—by the lion of Leo.

Around the date of Noruz, all Iranian householders, whether Zoroastrian or not, set up a table bearing the haft-seen, or “seven Ss”, a display of food items that is the modern equivalent of the ancient practice of setting out food to honour the spirits of the deceased. There is no standard configuration for the display, but it commonly includes:

| Sabzeh | green sprouts from wheat, peas, or barley |

| Samanoo | pudding made from sprouted grain |

| Serkeh | vinegar |

| Seeb | apples |

| Seer | garlic |

| Sumakh | powdered sumac seasoning |

| Senjed | small date-like fruits |

In Zoroastrian belief there are seven emanations of God known as the Amesha Spentas, “bounteous immortals”, and although there is no direct correspondence between the items on the table and any particular Amesha Spenta, the fact that there are seven can be seen as an allusion to them.

The Noruz table also commonly contains sonbol, a hyacinth or narcissus in bloom, sekeh, coins symbolizing prosperity, and the sofreh or decorative cloth on which everything is displayed. In addition to other symbolic items Zoroastrian families will include a picture of Zarathustra and a copy of the Avesta, the Zoroastrian holy book.

During the days following Noruz, believers will hold a jashan, a religious service during which the sacred fire is lit and the congregation renews its commitment to their religion.

**Palace and ritual centre located in southwestern Iran built by the Achaemenid kings of the first Persian Empire (c 600-330 BCE). Other carvings at Persepolis show processions of nobles and representatives of the various peoples of the Empire bringing gifts to the king during the festival of Noruz.