Enough is enough!

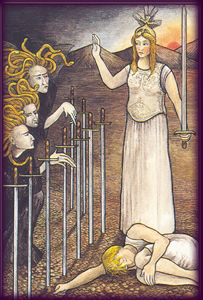

The goddess Athena puts

an end to Orestes’ ordeal

(Image

from the

Mythic tarot

© Liz Greene and Juliet Sharman-Burke)

You

wish to be considered righteous,

but not to act with justice.

The goddess Athena, from “The Oresteia” by Aeschylus,

458

BCE

Feelings of injury and the desire for retribution are part of the human condition; so, too, remorse and the difficulty of knowing when to let go of one’s guilt. The story of Orestes and the curse of the house of Atreus is one of the most powerful of the myths that picks up this theme. Son of the Greek general Agamemnon, Orestes gets caught in a terrible conflict when his mother, Clytemenestra, murders his father. Clytemenestra is acting out of grief and rage, for Agamemnon had sacrificed their daughter to ensure glory in the battle of Troy; however the god Apollo appears to Orestes and demands that he avenge his father’s death by killing his own mother.

Like many individuals enmeshed in difficult family situations, Orestes finds himself in an impossible fix. If he carries through Apollo’s orders, he will be pursued by the Furies, ancient goddesses of matriarchal law; on the other hand, if he refuses, the god Apollo has assured him he himself will strike Orestes dead. Afraid for his life, he reluctantly fulfils the god’s demand and kills his mother—at which point the Furies indeed begin their pursuit.

Run into the ground, Orestes appeals to Athena, who, questioning the rigid code—on both sides—that would demand he be put to death, establishes the principle of trial by jury and selects twelve local citizens to judge Orestes’ case. The jury is stalemated, six voting on the side of Apollo, six for the Furies. Just as Orestes is on the point of expiring, Athena intervenes on his behalf, putting an end to the ancient curse and curtailing his ordeal.

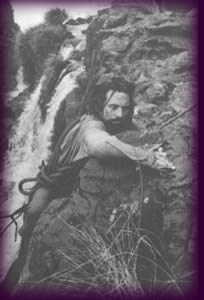

Burden

of guilt: Mendoza’s

ordeal of repentance

(from the film “The Mission”,

1986)

Released from his penance Menodoza finds self-forgiveness and healing for his spirit. He joins the mission as a priest, his ultimate destiny being to use his soldierly skills to fight for the Indians. He dies at the side of Father Gabriel, knowing that, although they chose different paths—in Mendoza’s case to fight, in Gabriel’s a non-violent protest—in the end each was living their ma’at, their individual truth.

"Which

is easier: to say, ‘Your sins are forgiven,’

or to say,

‘Get up and walk’?" ...

[Jesus]

said to the paralyzed man,

“I tell you, get up, take your mat and

go home.”

Luke 5: 23-24

Orestes was the victim of outer circumstances, but all of us are capable of being tormented by an inner conflict, for example that generated when outer criticism and demeaning treatment in childhood is internalised, and, Fury-like, continues to torture us well into adult life. In the story of the curing of the paralytic, Jesus clearly recognised an individual whose inner guilt and feelings of worthlessness had been literally crippling. He, like Athena, says “enough is enough”, cutting through the protests of those around him who question his right to offer forgiveness, and liberating the man from his burden of guilt.

A similar moment of grace is found in the 1986 film “The Mission”. Set in 18th-century colonial South America, the story follows the efforts of a small band of Jesuits to protect the local natives, the Guarani, from slavery. A mercenary and slavetrader, Rodrigo Mendoza, is imprisoned when he kills his own brother in a fight. The head of the local Jesuits, Father Gabriel, visits Mendoza in prison, and offers to take him to the mission. Mendoza accepts and in a self-imposed penance, makes the long, arduous journey through the jungle and up into the mountains dragging behind him the full weight of his armour.

When he reaches the top of the cliff where the mission is located, Mendoza finds himself face to face with the Indians whose relatives he had previously enslaved. A Guarani warrior seizes him and puts a knife to his throat, and in that moment of exhaustion Mendoza seems more than ready to die. But then with one swift stroke the Indian slices through the rope holding the armour; the huge weight of metal crashes down the mountainside, and freed from his burden, Mendoza gradually recovers a connection to the mystery of life.

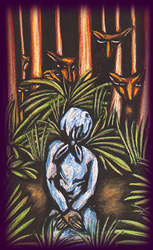

In

the New Orleans voodoo tarot

(© Louis Martinié and Sallie Ann Glassman) the authors have

chosen to represent the image traditionally named “justice”

as a woman entering the forest, voluntarily submitting to a confrontation

with the spirits. Represented in animal form, these spirits symbolise

her deep natural instincts with whom she wishes to re-establish relationship

and return to a more balanced way of life.

Self-forgiveness

is the key to the kingdom. It not only opens the door,

it’s the

hinges on the door,

it’s the key to the door, and it’s also the little bell that rings

and lets you know the door opened.

John-Roger*

Many individuals who have committed no outward crime nonetheless find themselves tortured by guilt and a sense of always falling short of the mark. Whilst such feelings can drive some people to great achievement, an individual burdened with an attitude that constantly demeans soon finds that the fruits of these successes are never truly satisfying. Once again, balance is the key, and learning to forgive and stand up for oneself is one way of turning these hypercritical inner judges into a resource capable of using the sword of discrimination to cut through impossible expectations.

It is a sign of maturity when we can accept the fact that right and wrong are often not clearly delineated, that the hardest ethical choices are those made alone and without communal consensus. As with Orestes, some of us find ourselves making horrible decisions in impossible situations. The fallout of this—the grist of guilt and remorse—can worry at our soul until, suddenly, one day, we find the pearl of self-forgiveness.

The sound of the shofar and the muezzin’s call to prayer are capable of evoking a yearning to reconnect to a sense of meaning, and for Jews and Muslims, the holy days of Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur and Lailat-ul-Bara’h are opportunities to stop and consider where lives have become wayward. For the rest of us it is necessary to keep an eye out for the oracle. To find our own time to shed unnecessary burdens—to forgive even the most grievous harms and be open to moments of mercy—so that order can be restored and the heart can find its balance. And whatever our personal belief, to consider the true miracle that humans have an inate capacity to, at times, experience a sense of meaning.

*Founder of the nondenominational Church of the Movement of Spiritual Inner Awareness.