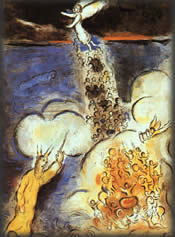

The parting of the red sea

by Marc Chagall

“Then

Miriam the prophetess, Aaron’s sister, took a tambourine in her

hand, and all the women followed her, with tambourines and dancing. Miriam

sang to them: Sing

to the LORD, for he is highly exalted. The horse and its rider he has

hurled into the sea.”

Exodus 15: 20-21

The Jewish festival of Pesach, or Passover, is one of the three major festivals of Judaism with both historical and agricultural significance. Agriculturally it represents the beginning of the harvest season in Israel. However the primary observances of the festival are related to the liberation from slavery and the flight from Egypt of the ancient Israelites, as told in the biblical book of Exodus.

‘Pesach’ derives from a Hebrew root word meaning ‘to pass over, to spare’, hence the English name of the festival. It is a reference to the belief that the god Yahweh passed over the Israelites when he was slaying the first born of Egypt. This was the final of ten plagues affecting Egypt, sent— accordinging to biblical view—by Yahweh to the Egyptian pharaoh as a punishment for keeping the Israelites in slavery.

According to the biblical account, in spite of initially allowing the Israelites to depart, the pharaoh changed his mind and went after them. Through his prophet Moses, Yahweh led the Israelites to the Sea of Reeds (the original Hebrew is yam suph, which actually means ‘Reed Sea’, not the Red Sea featured in early English translations), and then gave Moses the power to divide the water. Then, when the Israelites were safely across, the sea was allowed to close over again, engulfing the pursuing army.

There have been many efforts over the years to relate biblical places and events to their historical counterparts. To this day there remains wide disagreement as to the precise identity of such basic landmarks as the Sea of Reeds and Mount Sinai. One school of thought holds that Moses led the escaping Israelites across the Gulf of Suez at ebb tide, then watched as the water rose to its customary six and a half feet and drowned the pursuing Egyptians. An alternative theory is that they crossed Lake Sirbonis, one of the lakes to the east of the Nile which is separated from the Mediterranean by a narrow isthmus; the surrounding land is swampy and treacherous and the isthmus itself is frequently submerged during storms. The ten plagues described in the biblical account—lice, pestilence, locusts, boils, etc—are all commonplace features of life in Egypt. The rising of the Nile in spring brings floating micro-organisms that colour the water red, perhaps accounting for the first of the plagues: the turning of the water into blood.

From

this vantage point, it is probably impossible to discover the reality

of what happened. What does seem clear is that a group of slaves managed

to escape while their overseers were preoccupied. And that this escape

felt ‘miraculous’, and for generations to come would be celebrated

as such.

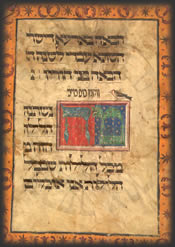

15th century Passover Haggadah

(haggadah, ‘narrative’)

Then Moses said to the people, “Commemorate this day, the day you

came out of Egypt, out of the land of slavery,because

the LORD brought you out of it with a mighty hand. Eat nothing containing

yeast.”

Exodus 13: 3

Jews have been celebrating Passover since about 1300 BCE, following the rules laid down in the second book of the Bible (Exodus, chapter 13). For example, in the passage quoted above, they are forbidden from eating anything containing yeast, and before Passover can begin, the house must be cleaned from top to bottom to remove any traces of leaven, commemoration of the fact that the Israelites did not have time to let their bread rise when they were ordered by Moses to flee.

Passover typically lasts from 6-8 days, the highlight occurring on one of the first two nights, when friends and family gather for the seder. Seder means ‘order’ and the sequence of ritual and narrative to be followed during the meal can be found in special books known as Haggadah. Each item in the meal is replete with symbolic significance, for example bitter herbs (most often horseradish) representing the bitterness of slavery, the karpas (greens such as parsley dipped in salt water) to represent tears, and charoset (a paste made of fruit, nuts and wine) which is meant to symbolise the mortar used by the slaves during their forced labour.

“Why

is this night different from all other nights?”

(Mah Nishtanah, the asking of the four questions, from the Maggid,

or story portion of the seder)

The word ‘synchronicity’ is given to the perception of meaning in a random confluence of chance occurrences. This is not to suggest that life isn’t intrinsically meaningful, but rather that the ability to experience events as fated or divinely orchestrated is one of the mysteries of human existence. Even if the escape from slavery was nothing more than a lucky break, it remains a defining moment in the forging of the Jewish identity. Through the remembrance of these events during Passover, Jews reaffirm their relationship with the power they believe responsible for their liberation; in the seder barech—the grace after meals—a cup of wine is poured and a door opened for the arrival of the prophet Elijah, symbolising their desire to keep the channels of revelation alive.

It is all too easy, when reading a sacred history such as recorded in the book of Exodus, to either dismiss it as ‘myth’ or the product of a superstitious mind. Or, if we are determined to maintain belief, to think that events were different in ancient times, that somehow the supernatural was more visible. However I believe it is important to realise that the material world hasn’t changed, that both physical and psychic reality remain much the same as ever. And that what people experienced ‘back then’, we, too, are capable of experiencing.

To

believe or not to believe, perhaps that is the question. Yet for all of

us, whatever the answer, the festival of Passover can remind us of how

the taste of tears and the experience of good fortune are both part and

parcel of life. And to recollect those moments in our own personal experience

that we would set apart as ‘miraculous’, worthy of remembering

as “different from all other times...”